The rot starts at the source.

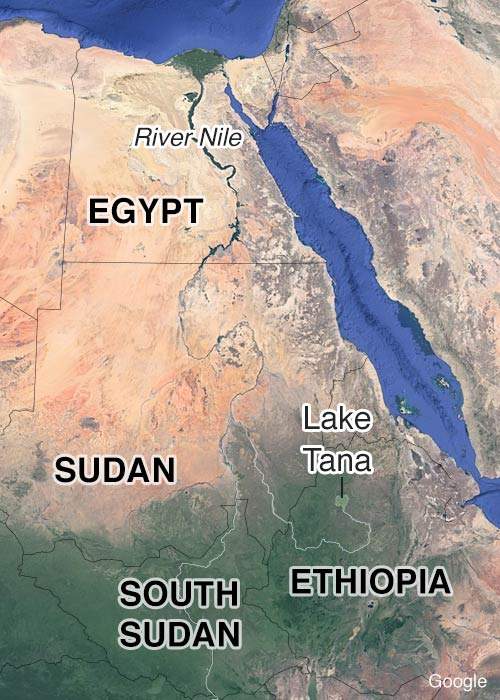

For as long as the Nile has flowed, Ethiopia’s rains have made up the great bulk – over 80% – of its waters.

Fat droplets pour down from July to September, not stopping until the roads have been churned into impassable bogs.

Small inland seas emerge almost overnight, slicing the Amhara Plateau into a maze of soggy islets.

Gushing out of a forest just south of Lake Tana, the Blue Nile greedily soaks up this bounty, quickly swelling from a stream to a torrent.

Though slightly longer, the White Nile, which originates in East Africa’s Lake Victoria and merges with the Ethiopian branch at Khartoum, carries a fraction of the volume.

But these rains are not falling as they used to. And that is potentially catastrophic for the entire basin.

The Meher, the long summer wet season, is arriving late, and the shorter rains earlier in the year sometimes not at all.

“It’s so inconsistent now. Sometimes stronger, sometimes lighter, but always different,” said Lakemariam Yohannes Worku, a lecturer and climate researcher at Arba Minch University.

When it does rain, the storms are often fiercer, washing over a billion tons of Ethiopian sediment into the Nile each year, which clogs dams and deprives farmers of much-needed soil nutrients.

Population growth has fuelled this phenomenon, as expanding families fell trees to free up more space and provide construction materials. Monster floods have also become much more common.

As crops wither and food prices soar, many rural communities, who have historically relied on steady rains rather than rivers to irrigate their land, have been pitched even deeper into desperate poverty.

Some villagers have given up on agriculture altogether, trying their luck instead in Bahir Dar, the regional hub – or nine hours’ bus drive away in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s booming capital.

Most have simply struggled on, subsisting on reduced rations while hoping against hope that the rains will normalize. Church attendance has increased, a priest told me.

For a small minority, however, enough is enough. Even in poor, out-of-the-way hamlets with no TVs or electricity, many have heard of the possibility of seeking their fortunes in Europe.

After dropping out of school to help his family work their battered farm and selling his prized bicycle to buy new seeds, Getish Adamu, a rake thin 17-year-old from Dangla, near the Blue Nile’s source, is among those considering chancing the perilous desert paths to the Mediterranean.

Getish Adamu is considering his future

“Myself, I am undecided. I would like to stay with my family,” he said. “But if these rains go on like this, I will not be able to stay.” If the Nile rains continue to ebb and flow, nor will many others.

The further the Nile goes, the more sordid its problems become.

Thirty miles after leaving Lake Tana, the river plunges over the majestic Blue Nile falls, and then enters a long web of deep cliff-lined gorges.

Gathering strength with each arriving tributary, it cascades down 1,500 metres from the highlands to the semi-arid plains below. It is the most beautiful, most isolated and, perhaps, the most troubled portion of the entire basin.

That is because Ethiopia’s sparsely-populated wild west is mired in squabbles both local and international.

From the controversial construction of Africa’s largest dam in the rugged hinterland just shy of the Sudanese border, to Addis Ababa’s alleged displacement of tens of thousands of villagers in order to lease their prime Nile-side land to foreign agribusinesses, an uneasy pall hangs over the entire area.

Just reporting there means navigating a complicated minefield of checkpoints, informants, and terrified interviewees.

“You have to understand there are things we cannot talk about,” said Samuel, a restaurant chef in Injibera, blanching noticeably when asked about nearby land grabs. “These are the questions that get you into trouble.”

He was not exaggerating. Days later, security forces raided my hotel room, taking only my reporting pads (and some of my Snickers stash). On another occasion, I was turned back at a police roadstop near Chagni while trying to reach some of the largest chunks of confiscated farmland.

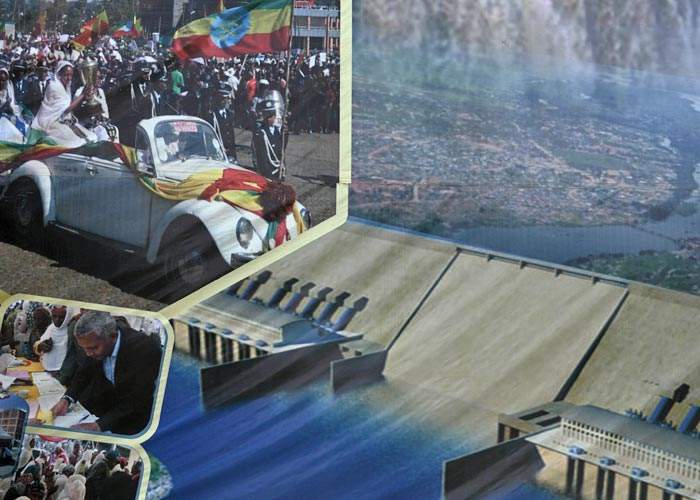

Of all these hot-button issues, it is the dam – the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) – that has really stoked the region’s hopes and fears.

GERD under construction in 2015

(Getty Images)

At a little over a mile long and with a generating capacity of roughly 7GW, the Nile megastructure is seen by many Ethiopians as a tangible illustration of their country’s emergence after the humiliation of the famines in the 1980s and 90s.

Roadside billboards superimposed with politicians’ faces tout its potential to br

ing electricity to millions; schoolchildren sing about it. “This is our destiny,” some of them chant. Across western Ethiopia, many residents excitedly await their new neighbour.

But to downstream Egypt, which is mostly desert, receives little rain, and consequently relies on the river for more than 95% of its water, the possibility that GERD might cut the Nile’s flow is perceived as an existential crisis.

A 1959 treaty apportioned all Nile waters to Egypt and Sudan, though Ethiopia and the other upstream riverine states dispute its legitimacy, saying it was drawn up in the colonial era when most African countries had little say in their own affairs.

There have been threats of war from Cairo, and fierce sabre-ratt

ling on both sides. If there is ever a regional conflagration over water, this stunning, almost impossibly green stretch of the river will likely be at the heart of it.

“It all looks so peaceful, no?” a naval officer called Moses told me over beers at a shoreline Bahir Dar bar. “But we are all aware that we are on the frontline. This is where the water is, the dam, the best land.”

Despite losing access to the sea when Eritrea broke away in 1991, Ethiopia has maintained a naval facility on Lake Tana. “We might need it in the future,” Moses added, cryptically.

BBC