Uganda is the most physically active nation in the world, according to a recent report by the World Health Organization. The BBC’s Patience Atuhaire went to find out why.

Jennifer Namulembwa spends an hour-and-a-half walking to work, five days a week. From Namuwongo on the south-eastern end of Uganda’s capital, Kampala, she navigates her way past the railway line and crosses the treacherous eight-lane stretch of the highway.

She skirts the plush Kololo hill, finally getting to Kamwokya suburb by 9am.

At work, the 34-year-old spends two hours on her feet, cleaning a three-floor building.

The rest of her day is spent running errands for her boss. And just after 5pm, she traces the same route, to return home.

“I’m used to it so I don’t feel the distance. I never wear nice shoes to work. I would also like to enjoy the good life sometimes; ride in a car or on a motorcycle,” she chuckles, showing her dusty feet in black sandals.

Her commute is not dictated by the size of her body, but that of her wallet.

Her salary is just over $100 (£70) a month. Domestic needs and her two children’s education burn through it, so she can’t afford to pay for transport.

At 7am, the sun casts long shadows of the many people trekking along the railway line.

Along the same route walks father-of-three Oprus Aduba, a hotel worker. Wiping sweat off his brow, he too says that the numbers have failed to add up.

The World Health Organization report on physical activity, which categorized Uganda as one of the most active countries in the world, probably had people like them in mind.

Changing lifestyles

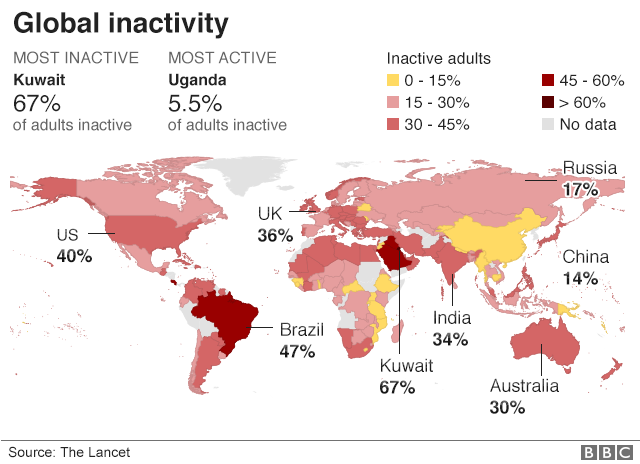

The study, tracking the level of physical activity around the world, found that only 5.5% of Ugandans had an insufficient level of activity.

Mozambique, Tanzania, Lesotho and Togo too are also doing quite well.

In comparison, people in Kuwait, American Samoa, Saudi Arabia and Iraq seem to be living highly sedentary lives. About a quarter of the world’s population don’t get enough exercise.

The research findings note that, generally, people in low-income countries seem to integrate a sufficient amount of physical activity in their lifestyles, unlike those in wealthier countries.

The poorer people are, the more likely they are to use modes of transport, or be in an occupation, that involve physical work.

However, the study, an analysis of self-reported national data, doesn’t explain why Ugandans are more active than other countries with a similar level of income.

Even in low-income countries, more people are getting into formal employment, spending long hours at the office, buying cars and eating more fast food, meaning Uganda might become less healthy as they become wealthier.

The two Kampala walkers are not even aware of the WHO-recommended 150 minutes of moderate-to-intense or 75 minutes of rigorous activity per week.

They easily surpass the target without trying.

Exercise guidelines for 19- to 64-year-olds

How much?

- at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity every week

- strength exercises on two or more days a week that work all the major muscles

- break up long periods of sitting with light activity

What is moderate aerobic activity?

- Walking fast, water aerobics, riding a bike on level ground or with a few hills,doubles tennis, pushing a lawn mower, hiking, skateboarding, rollerblading,volleyball, basketball

What counts as vigorous activity?

- Jogging or running, swimming fast, riding a bike fast or on hills, singles tennis, football, rugby, skipping rope, hockey, aerobics, gymnastics, martial arts

What activities strengthen muscles?

- lifting weights, working with resistance bands, doing exercises that use your own body weight, such as push-ups and sit-ups, heavy gardening, such as digging and shovelling, yoga

What activities are both aerobic and muscle-strengthening?

- circuit training, aerobics, running, football, rugby, netball, hockey

Source: NHS

Away from the city to rural Uganda, where an estimated 70% of the population work in agriculture, the study findings ring very true.

It seems that nothing keeps one in shape better than a hoe.

Abiasali Nsereko, a 68-year-old farmer in Luweero, about two hours north of Kampala, starts his day at 5am. Having finished milking the cows, real work starts.

It could be cleaning the cow shed, tending to the coffee bushes or the banana trees.

He works his 10-acre farm by himself, with the occasional hired labour.

“I spend about eight hours on my feet, six days a week. I grow all the food that we eat. If I stopped working, I would probably fall sick. At my age, I do not have a single ache in my body,” he says.

The joggers are coming

But it is not easy for those Ugandans trying to stay fit as their lifestyles change.

Kampala is not a fitness-friendly city. There are hardly any green parks, most roads have no pavements, and many cars emit the same amount of fumes as a grass hut on fire.

Walking or jogging demands some bravery. If you are lucky to find a walkway, you have to watch out for open manholes, and boda bodas (motorcycle taxis), which will push you off the pavement and top it off with insults.

Motorists will not be shy to drive you into the storm-drain, in which you have to jump over plastic bags that look very suspiciously like “flying toilets”.

Still, over the last couple of years, joggers, mostly the urban elite, have increasingly appeared on the streets.

There is also a growing trend of fitness groups around the city. On a sunny Saturday morning, three different groups work out in the parking lot of Mandela National Stadium, Namboole.

From people in their 60s to a nine-year old girl, they go through their jumps, squats and stretches.

To an outsider it may look like a fad, but Diana Nakabugo tells me that the group has kept her motivation up.

She’s at the stadium from 6.30am three times a week, for an hour’s work-out.

But it is a struggle. The pressures of a working life do not leave much room for recreational physical activity.

Ms Nakabugo says: “I wake up with traffic jam on my mind. You have to drop the kids at school, and then make it to work, on time. It’s a challenge. Many parents fail to prioritise exercise.”

Schools without playgrounds

I seek out the little girl when the session is over. For her, this is more about spending time with her dad.

Sabiti Matovu is a primary school physical education teacher who practises what he preaches.

But people like him are becoming rare in Ugandan schools.

“Physical education used to be on the timetable of every school. But here in the city, schools put emphasis only on academics,” he says, concerned about how the country will keep its youth fit.

“Many do not have playgrounds. In the rural areas where there is space, the schools don’t have PE teachers.”

Uganda’s first cycle lane

On 7 July, President Yoweri Museveni launched the National Day of Physical Activity, which will be marked annually. But it will take more than a presidential gesture to keep Uganda active.

Amanda Ngabirano, a lecturer in Urban Planning at Makerere’s College of Engineering and Technology calls herself a “cycologist”. She drives from home with her folding bicycle in the boot, parks halfway to work, and cycles the remaining 7km (4 miles).

My jaw drops when she says: “I pick out the roads with the most traffic.”

Imagine cars swerving from one lane to the other, jerking to a sudden stop, boda bodas weaving through any available gap, matatu drivers hooting and screaming out the windows. Add a woman on a bicycle.

“There is order in that chaos. The drivers are going slowly, and they can see me. It’s safer than the upmarket roads with fewer cars because there everyone is speeding,” she explains.

Her crusade to get the city infrastructure upgraded to provide for non-motorised modes of transport has seen the ministry of works develop its first policy along those lines.

Her work may be part of the reason why, less than a month ago, the Kampala Capital City Authority marked out the first bicycle lane in Kampala. The 500-metre lane is in leafy Kololo, but it is a start.

The country may be celebrating the WHO study, but Uganda is rapidly urbanising.

In the next couple of decades, there are likely to be fewer 67-year-olds still fit to till the land, and more people behind the wheel in traffic snarl-ups.

Roy William Mayega of the Makerere School of Public Health did a study in the peri-urban areas of Iganga district, east of the capital, in 2013. He found that Ugandan lifestyles are changing.

“We found that 85% of the participants were physically active. We assessed blood sugar and weight as well. The 15% who were not sufficiently active were twice as likely to have diabetes and high blood pressure than those who were active,” he says.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESDr Mayega warns that the number of Ugandans interested in sectors which require rigorous effort such as agriculture is shrinking, especially among the youth.

No fancy gadgets

He also noticed a shift in the food environment. In every small roadside town, young people were cooking high-calorie, processed-flour foods, and people were coming from the villages for a taste.

“Physical activity is becoming less of a lifestyle, and we have started to eat things we didn’t in the past, but the people’s perceptions of recreational activity are still negative. One man in the study told me: ‘Playing is for children’,” he says.

All that plays into the rising risk and cases of non-communicable diseases.

For now though, most Ugandans are keeping fit without fancy gadgets to count their daily steps and monitor their calorie count. But the country will need a national consciousness and the right infrastructure, to retain its top-shape position.

BBC